Today is 16 March 2020 and I am writing this post to “clear

the air” regards to the realities and challenges of the ongoing COVID-19 crisis

that is striking the globe. Now, I am

not a medical professional, an immunologist, a public health professional, or

even a biologically focused person. I

do, however, listen and know many of these people. I also read carefully and respectfully what

the experts are putting out for us to digest.

This said, however, I am also a person that knows quite a bit about

emergency planning and emergency response thanks to specific assignments and experiences

in the US Army.[1] Further, in my work at George Mason University

and at Clarkson University studying and executing preparations to build resilience

of campuses and communities, I can also speak to how we can and should react so

as to best mitigate the effects of any kind of disaster, including an infectious

disease crisis. It is from that

perspective, therefore, I will begin and end this discussion.

To begin with, resilience, simply put is the ability of a

system, a society, or an individual, to “bounce back” from a disruption, trauma,

disaster, or other stressor. Here is how

Merriam-Webster defines reliance:

“noun

1: the capability of a strained

body to recover its size and shape after deformation caused especially by

compressive stress

2: an ability to recover from or

adjust easily to misfortune or change”[2]

To that end, one of the most popular ways to depict and

describe the topic of resilience is using the reliance curve (also known as the

critical functionality curve for resilience) as illustrated in Figure 1:

Figure 1. General form of the resilience curve as defined by

rebound

For more on this curve, what it describes and useful for as

well as its critiques and limitations, please watch this very informative set

of videos by a colleague of mine, Dr. Thomas Seager of Arizona State

University, made with others from the Naval Post Graduate School, in the area

of speaking about infrastructure:

Critical Functionality Curve (1 of

3) for Resilient Infrastructure – Explanation:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uX9Evd5374s.[4]

Critical Functionality Curve (2 of

3) for Resilient Infrastructure – Critique:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSIYsyDyEdw[5]

Critical Functionality Curve (3 of

3) for Resilient Infrastructure – Alternatives:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1OhvCzDF74[6]

Thus, what is critical to understand is that the recovery

time and total functional rebound from an event is dependent upon the depth of absorption

required of the system, society, or individual.

To that end, efforts to build resilience focus on how to both minimize

the stressors as well as increase the capacity to absorb said stressors. Thus preparation and learning can aid in the latter

(capacity to absorb) and anticipation of, and adaption during, the acute trauma

or stress enables the ability to aid in the former (minimize the stressor). In the current crisis regarding the COVID-19

outbreak, we are no longer in a preparation stage nor are we in an anticipation

stage (it is here). While we are

certainly constantly learning, where we are now is in the stage where we need

to adapt in order to mitigate the depth of absorption our systems must take,

lest they are unable to recover.

This brings us then to the nature of this crisis and the

nature of what the COVID-19 virus means to our social and medical systems. One of the best ways to get a handle on what

the COVID-19 crisis is doing is to check out the John’s Hopkins live mapping

tool for tracking cases of the disease: https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6. What is important to track is the graphic on

the bottom right of the chart, shown here as Figure 2:

Figure 2. COVID-19 Virus spread over time, as of 16 March 2020

So you will note, in this tracking tool, that while the rise

in Chinese cases occurred earlier (late January through mid-February), the rest

of the world is having a much higher spike (driven largely by the European

cases) well in advance of the rate of the Chinese cases per day. The Chinese rate of infection, we have to

remember, was, in part, initially hidden but also a result of extreme

restrictions on behavior, which have now resulted in a leveling out of the

infection rate. What we are seeing

elsewhere ought to alarm us, as we have seen situations like this before,

historically, and in open societies, we are wont to take the draconian measures

the Chinese have taken.

Let us touch first on the history. In 1918, at the end of World War 1, an

outbreak of a new disease, termed “the Spanish Flu,” broke out across the

world. This virus was not traditional

influenza, but an H1N1 avian flu disease.

What makes this similar to the contemporaneous COVID-19 outbreak, is

that this was a novel virus that had not struck before. For that reason, like today, “[w]ith no

vaccine to protect against influenza infection and no antibiotics to treat

secondary bacterial infections that can be associated with influenza

infections, control efforts worldwide were limited to non-pharmaceutical

interventions such as isolation, quarantine, good personal hygiene, use of

disinfectants, and limitations of public gatherings, which were applied

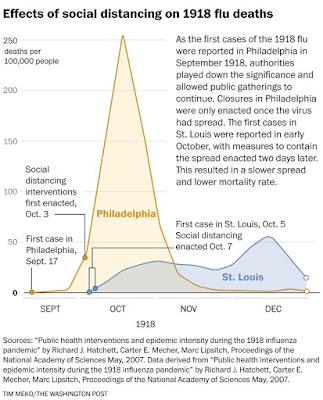

unevenly.”[8] To that note about uneven application, the

following chart, Figure 3, is illustrative of the effects in two communities, Philadelphia,

PA and St. Louis, MO.

Figure 3. Effects of social distancing on the 1918 flu epidemic

Succinctly, the chart illustrates what happened when social

distancing, as an adaptive measure, was applied and when it was not. The consequence was that failure to implement

an effective adaption strategy resulted in system overload and a serious spike

in deaths as a result of the outbreak. Returning

to the resilience curve, the system was not able to absorb the impact and thus

resulted in many more deaths than when adaptive measures were employed. As is seen in the St. Louis case infections

and deaths still occurred, but that both the intensity (number of deaths per

day) as well as the magnitude (total number of deaths; area under the curve)

was minimized. Again, when it was a

novel disease outbreak, a stressor to use resilience language, adaptive

measures were critical to ensuring a better rebound and recovery from the disaster.

Many have inappropriately categorized this outbreak as being

nothing other than a “flu breakout”, going as so far as to say and cite that

there have been more deaths as a result of influenza this year, so far, as have

been from COVID-19. Were this 1918, that

might be an apt comparison, but this is 2020.

As such, when it comes to influenza in 2020 as it compares to COVID-19

in 2020, several things are critical to consider. First, for the flu we have a vaccine and we

have treatment regimens that don’t require hospitalization in large numbers

within short periods of time. Second,

making it worse, the mortality rate (number of deaths per incident of known infection)

is higher than we see in contemporaneous flu strains,[10] both as a consequence of

the lack of a good preventative as well as its mode of attack in the body.[11] Third, this is a novel virus, so tracking the

cases has not been as good as we do with the flu, but what we’ve seen so far is

much more concerning.[12] Fourth, the rate of infection (the slope of

the curve), is not as steep for flu (illustrated in Figure 4) as for COVID-19

(illustrated in Figure 5). So the

problem here is the RATE of infection is exceptionally high (we are currently tracking

with Italy and Iran) with a treatment requirement that uses a high amount of

resources (it’s a pneumonic disease requiring ventilators in many cases),

without a known pharmaceutical solution (either as a vaccine or a drug

treatment regimen).

Figure 4. Cumulative Rate of Confirmed Influenza Hospitalizations

Figure 5. Cumulative Rate of Confirmed Influenza Hospitalizations

Returning then to resilience as a way to analyze this

problem, what is needed is to slow the rate of infections to allow us to a) buy

time so we can get a better non-hospital treatment in place (which may not

happen for another 12-18 months),[15] and b) not overwhelm the

limited hospital based resources we have (roughly 35 ICU bed per 100,000,

unevenly distributed around the country).[16] To do that, we need to do things to slow the

spread and prevent those most vulnerable from getting it inadvertently (noting that,

again unlike the flu, the incubation period can be over 14 days from contact to

symptoms appearing).[17] This means, to use a hypothetical, that 4th

grade Julie can have contracted the virus from neighbor Bill and consequently

share it with her whole class including Bobby, Shelly, and Bart who all live

with their ailing grandparents who are particularly susceptible and have a

higher mortality rate. What we need to

do is follow the public health recommendations to keep physical separation and

work to curtail anything non-essential.

The reason for this is that what has been termed “social distancing” is

an adaptive tool that has proven effective to slow the rate of the spread of

the disease, so as to make its transmission and treatment manageable. This is illustrated in the chart below,

Figure 6.

Figure 6. Social distancing effect on cumulative cases of corona

virus

All of this requires us to maintain a level head and manage

the adaption process carefully but swiftly so as to address the crisis in the

best way possible. Our goal is to engage

in adaptive capacity while at the same time not compromising the systems that

are responsible for absorbing the impact of this stressor. To that end, we need to take this in a

measured serious way. For instance, we

need to recognize that by running out and hoarding goods, we are likely to make the

situation worse or take away from those in greater need than ourselves. We still need to have access to basic needs

and we still have to have the ability to have medical services operate

effectively. This means we’ve got to

have truckers on the road and shippers shipping and fuel stations for the

above, and so on and so forth. Yes, we

need to keep all of that to a minimum, and we need to keep the interactions

between everyone to as small a set of numbers as possible, but we can’t “close

everything”, otherwise we’ll exacerbate the problem by not getting the needed

supplies and personnel to where it’s needed as well as have people not having

the things they need to survive at home.

We also need to recognize that what we are trying to do is to slow the

rate of infection, not stop the infection itself. We can’t currently stop it (as articulated

above) and engaging in mass psychosis about being infected will only heighten

fears that lead to non-rational behaviors and longer term damage than the

disease itself.[19]

So, what do we need to do to accomplish that. First, we need to minimize our physical space

contact with one another. Avoid large

gatherings, avoid places where significant infection is underway, and avoid

doing anything that is not necessary.[20] If you can work from home, we need to move to

that mode. Further, we need to support mission

critical workers (health workers, emergency management professionals, military

members, public service employees, key logistics support members, etc.) with

having patience and forgoing on-demand items as well as only buying and getting

what you need. Luckily, we have

technology we can rely on to make much of this happen. But we also have to recognize not everyone is

so equipped, so we also need to look out for our neighbors and families and

help where we can.

Next, get with your public officials and deliver the message

that they need to lead us by telling us we have to make some sacrifices in the short-term

hardship now to avoid widespread devastation later. Do so, however, by telling them to shut-down

all non-essential services and carefully keep running, and manage well, the

absolutely minimally essential services and goods to see us through. Do NOT insist on having them “close

everything,” which will only stoke fear and cause problems for the overall

response system that we are relying on.

To that end, public language needs to be very clear to say what we mean

and mean what we say. This means we have

to have leadership not obscure facts nor heighten fears, but instead provide

steady, concerted and concerned messaging that follow the best advice our

public health community can provide us.[21] And these leaders do have to make the tough

choices that will require us to forgo wants (as compared with bonafide needs) until we can have better handle on

the rate of infection and have treatments that can mitigate mortality rates

across the board.

Finally, we ought to remain humble enough to pray or

otherwise connect with our spirituality.

Some may see this assertion as inappropriate for an otherwise

academically focused post. That,

however, is actually false. Spirituality

has been shown in several studies to be a key coping mechanism that enables greater

resiliency to traumas.[22] To that end, if not already making this

connection, I would encourage us to do so amidst this challenge to ourselves

and our broader society. This may not be

by going to your normal worship services if that is your norm, but it does mean that we should

connect with one another and with our spiritual side to enable us to have the necessary

hope from which to build as we recover from this stressor. We are in this together and its key that we

make that a priority.

To conclude, what we in the resilience community know is

that we need to do our best, in the midst of a crisis to adapt and to minimize

the core disruptions so that we can reduce the depth of impact and amount of

time to recovery. This is not the end, this isn't the Black Death, but a disruption; one we can and will recover from. To that end, we need

to do all of the above to stay resilient and enable us to come out as well as

we can on the other side. Thanks and all

the best to you and all of us in these challenging times.

[1]

one of which was a 3-year stint at a FEMA liaison officer at the Pentagon

dealing with many a crisis from Super-storm Sandy to fires in California to the

Ebola virus outbreak in west Africa.

[2]

“Definition

of RESILIENCE,” accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/resilience.

[3]

Azad

M. Madni, Dan Erwin, and Michael Sievers, “Constructing Models for Systems

Resilience: Challenges, Concepts, and Formal Methods,” Systems 8, no. 1

(March 2020): 3, https://doi.org/10.3390/systems8010003.

[4]

Critical

Functionality Curve (1 of 3) for Resilient Infrastructure - Explanation,

accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uX9Evd5374s.

[5]

Critical

Functionality Curve (2 of 3) for Resilient Infrastructure - Critique,

accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HSIYsyDyEdw.

[6]

Critical

Functionality Curve (3 of 3) for Resilient Infrastructure - Alternatives,

accessed March 16, 2020, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L1OhvCzDF74.

[7]

“Coronavirus

COVID-19 (2019-NCoV),” accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.arcgis.com/apps/opsdashboard/index.html#/bda7594740fd40299423467b48e9ecf6.

[8]

“1918

Pandemic (H1N1 Virus) | Pandemic Influenza (Flu) | CDC,” June 26, 2019,

https://www.cdc.gov/flu/pandemic-resources/1918-pandemic-h1n1.html.

[9]

Carolyn

Y. Johnson et al., “Social Distancing Could Buy U.S. Valuable Time against

Coronavirus,” Washington Post, accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.washingtonpost.com/health/2020/03/10/social-distancing-coronavirus/.

[10]

“No,

Coronavirus Isn’t ‘Just Like The Flu’. Here Are The Very Important Differences,”

accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.sciencealert.com/the-new-coronavirus-isn-t-like-the-flu-but-they-have-one-big-thing-in-common.

[11]

“Yale

New Haven Health | Influenza (Flu) vs Coronaviruses,” accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.ynhhs.org/patient-care/urgent-care/flu-or-coronavirus.

[13]

CDC, “Weekly

U.S. Influenza Surveillance Report (FluView),” Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention, March 13, 2020, https://www.cdc.gov/flu/weekly/index.htm.

[14]

Dylan

Scott, “How the US Stacks up to Other Countries in Confirmed Coronavirus Cases,”

Vox, March 13, 2020,

https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2020/3/13/21178289/confirmed-coronavirus-cases-us-countries-italy-iran-singapore-hong-kong.

[15]

“Coronavirus

Vaccine: Development, Timeline, and More,” accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/coronavirus-vaccine.

[16]

“SCCM

| United States Resource Availability for COVID-19,” Society of Critical Care

Medicine (SCCM), accessed March 16, 2020,

https://sccm.org/Blog/March-2020/United-States-Resource-Availability-for-COVID-19.

[17]

Tomas

Pueyo, “Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now,” Medium, March 15, 2020,

https://medium.com/@tomaspueyo/coronavirus-act-today-or-people-will-die-f4d3d9cd99ca.

[19]

“How

Fear of Contagious Diseases Fuels Xenophobia,” Stanford Graduate School of

Business, accessed March 16, 2020,

https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/how-fear-contagious-diseases-fuels-xenophobia.

[22]

Julio

F. P. Peres et al., “Spirituality and Resilience in Trauma Victims,” Journal

of Religion and Health 46, no. 3 (September 1, 2007): 343–50,

https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-006-9103-0.